When Microsoft launched the original Xbox back in 2001, it was keenly aware that the console would live or die by the quality of its exclusive games. It was going up against Sony and Nintendo – two companies with enviable reserves of internal development talent – and a strong slate of must-have Xbox games was a must if players were going to be convinced to jump ship to this new system. While it wasn’t available at launch, Lionhead’s Fable would prove to be one of the most important Xbox exclusives – but its path to market was anything but straightforward.

In fact, Fable’s origins predate the Xbox by quite some time. The game was born within the walls of Big Blue Box, a tiny British satellite studio spun-off from Peter Molyneux’s Lionhead by siblings Dene and Simon Carter. "Simon and I had wanted to do our own thing for quite some time," explains Dene. "But lacking anything in the way of funds, industry clout, or even a place to work – we were initially based in Peter’s house in Guildford – Lionhead’s offer to start something with their help seemed like too good an opportunity to pass up." It was the fulfilment of a long-term ambition for the pair, who had joined Bullfrog – Molyneux’s previous studio – and worked on seminal titles such as Dungeon Keeper before moving to the newly-established Lionhead following EA’s purchase of Bullfrog and Molyneux’s departure.

But lacking anything in the way of funds, industry clout, or even a place to work, Lionhead’s offer to start something with their help seemed like too good an opportunity to pass up

Given today’s obsession with massive teams producing AAA titles, the notion of splintering off a smaller studio from a larger one might seem counterproductive, but Simon feels there were a great many benefits. “Peter was a big name at the time, which really helped to open doors; Lionhead had a business and legal team who helped us with the practicalities of running a business, which were new to us. In general it allowed us to focus on developing the game, rather than worrying about the other stuff.” Dene is in agreement. “It benefited us in numerous ways; from having real business partners who knew how to negotiate, to help securing a bank loan, to general advice and legal resources. There’d have been no Big Blue Box without Lionhead.”

After relocating to the sleepy market town of Godalming, Surrey – which Fable artist Damian Buzugbe describes as being famous for "an angry swan that would attack you if you got near it and a possible sighting of Sue Barker in the local Waitrose" – Big Blue Box set to work on the Carter brothers’ dream project: a landscape-altering, wizard-against-wizard 'Battle Royale' game called Wishworld.

"When we started Big Blue Box we had a pretty long list of game ideas, which we’d ordered in terms of risk, viability and our passion to make it," explains Simon. “At the top of the list was Wishworld, a sort of third-person RTS that took the magic and world-morphing aspects of Magic Carpet and combined them with elements of one of our favourite games, Julian Gollop’s Chaos. It was a very ‘Bullfrog’ game; multiplayer first, magical, technically ambitious." In fact, it was a little too ambitious, and the team found that convincing a publisher to take the punt and fund the project proved to be difficult.

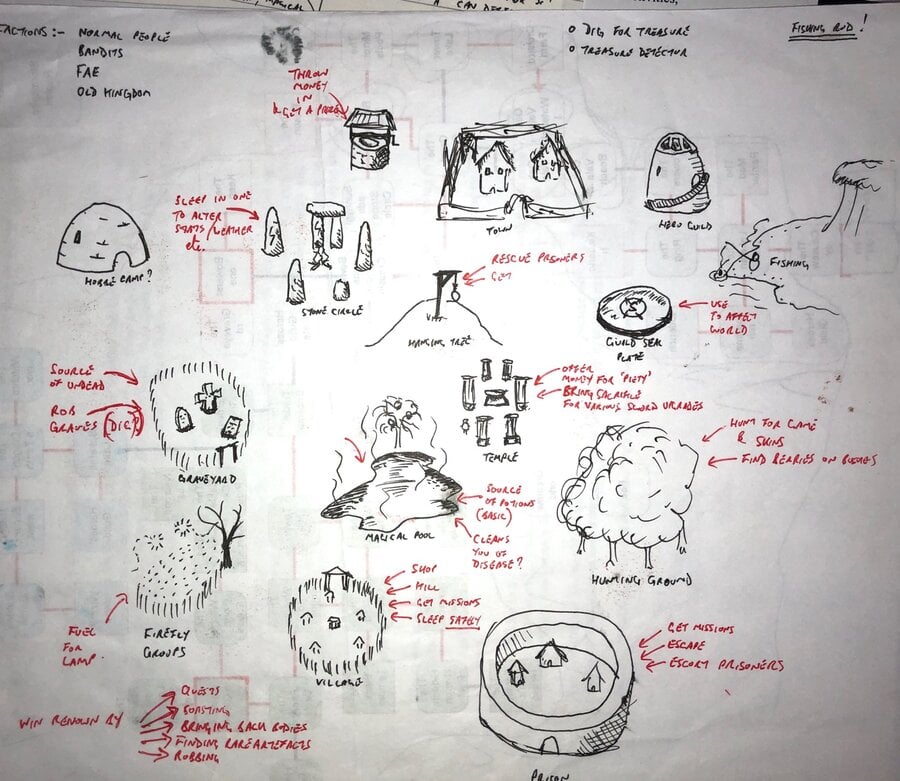

"After nearly two years of having publishers tell us that there was no market for such an odd thing – and Shiny Entertainment’s Sacrifice, a nearly identical premise, coming out a mere 8 months after we’d talked to 14 of their publishing folks – we knew something had to change," says Dene. "We talked things over with Peter who suggested we shift it into more of a single-player, character-driven game." Luckly, this transition was relatively easy for the studio. “Second on our list of game ideas was something Dene and I had been talking about for years, based on our love of Ultima games and Jim Henson’s The Storyteller – a fairy tale RPG where the world was a nonlinear sandbox simulation," says Simon of the concept that would ultimately become Project Ego – later renamed Fable. “Ironically, given how much more ambitious and difficult it was compared to Wishworld, we had far less difficulty getting publisher interest in Fable than Wishworld."

Ironically, given how much more ambitious and difficult it was compared to Wishworld, we had far less difficulty getting publisher interest in Fable than Wishworld

"Peter’s suggestion was that we focus on one wizard, Merlin, but allow players to make any kind of Merlin they want," explains Dene. "We liked some aspects of that idea and decided to push it a little further, making it into a game where players could become any kind of heroic archetype they wanted. We had initially wanted to stay away from a morphing character as we didn’t want to cannibalise the unique selling point of Black and White, Lionhead’s first game, but Peter gave us his blessing. Two of our earliest hires – Martin Bell and Kaspar Daugaard – took these ideas and ran with them, creating an engine capable of morphing detailed characters with wrinkles, tattoos, and body morphs as well as forests, grass and a bunch of other features that were quite remarkable for the time."

Indeed, Fable remains an incredibly ambitious game, even by modern standards. The pitch was tantalizing, especially for gamers at the turn of the millennium who had been raised on RPGs which led them down a very narrow path and did little to encourage player agency and experimentation. In Fable, you could shape your character and the world around you via your actions, choosing to be a force for good or giving into your darker side and causing all kinds of mischief – and your character would change their appearance based on your actions. This was backed up by a massive, immersive game world in the form of Albion, as well as a real-time combat engine, a host of fully-voiced NPCs and much more besides. It was an epic undertaking – especially for such a small (and largely untested) studio.

Artist Damian Buzugbe is one of the people responsible for Fable’s unique look, and was a relatively late addition to the team at Big Blue Box. He recalls listening to Dene’s outline for the game during his initial job interview. "It was a beautiful pitch of a hero in this dark fantasy world, but instead of just playing along to someone else’s story, you could shape it. He spoke in detail of you as a hero passes some bandit on the trail and your actions not only change the nearby village’s future, but also that of the bandits. It was the most ambitious game idea I had heard in a long time and I had to help make it – then he dropped in that your choices shape your character, too. Little did I know this would come to haunt me as a character lead."

While Fable didn’t begin life as an Xbox exclusive – it was in development for the Sega Dreamcast at one point – it would be Microsoft’s involvement that elevated the project to a whole new level of importance. "When I joined in 2000, Microsoft were already on board, which was excellent as they were developing this brand new, crazy-looking console," recalls Buzugbe. "What better fit than this brand new crazy-looking game. It seemed perfect to me."

If the PS2 was an elegant Japanese bento box, the Xbox was a flame-grilled double-whopper with extra cheese

The sheer size of Microsoft’s new console was a surprise when the team first laid eyes on it, however. "The Xbox design wasn’t exactly restrained," chuckles Simon. "If the PS2 was an elegant Japanese bento box, the Xbox was a flame-grilled double-whopper with extra cheese." Buzugbe is in agreement. "You couldn’t get a bigger, louder and brasher-looking console than that. That thing had room for a family of four to easily sit around it and still have room to invite granny round." The massive 'Duke' controller was also a point of contention. "At that point, we had the controllers that were the size of a large roast dinner, and about as easy to handle," says Dene. "Out of sheer frustration, we stole a couple of the smaller Japanese 'Controller S' joypads during one E3 show. A year later we ran into some bugs on the controller driver and, rather helpfully, reported this to Microsoft. They said: 'Uh… you’re using controller 3.5.275b. You shouldn’t have those! Where did you get…' – at which point we put down the phone and tried to pretend the whole incident had never happened."

Looks aren’t everything, of course, and the system proved to be more agreeable when it came to raw processing power. "It was basically a PC in a box which – for PC developers fresh off Dungeon Keeper – was a joy," remembers Dene. "The fact that it had a hard disk allowed an element of permanence in the world, so every action players performed could affect each of the individual villagers. Without a hard disk this would have been next to impossible." His brother concurs. "Fable could not have existed without the hard drive. We had a huge number of textures, animations, sound effects and meshes; the game was nonlinear, so we didn’t know which assets would be needed up front; and the hero – and to a lesser extent, the NPCs – were all made up of these Lego sets of dynamic pieces that could morph. Everything was streamed in Fable – we were piping 100s of megabytes of assets through a tiny 32 megabyte memory cache." For Buzugbe, the power of the system was instrumental in achieving his aims. "The graphics that Martin, Kaspar and the engine team created on that beast were stunning. Having been used to the PS2 at home, this was a giant leap for big-footed Albion villagers. I think it was one of the best-looking games out there."

Fable’s look is quite unlike any other RPG of the period, and Buzugbe played a considerable role in creating those unusual proportions. "When I joined the team we were still searching for an art style, having tried ‘realistic’ and quite a few styles in between. One day we had a brainstorm around the hero where everyone who could pick up a pencil threw down their pitch. At the time I was a huge fan of Joe Madureira and his work on Battle Chasers; also, I had been reading manga for years so my drawing style reflected that. My sketches of the hero and some bandits with these bizarrely-proportioned hands, feet and expressive eyes stood out quite a bit."

With Microsoft on-board and the game locked down as an Xbox exclusive, the team’s lofty goals suddenly seemed within reach, and the platform holder wasted no time in assigning some key talent to assist in production. "We were very fortunate to have an extremely enthusiastic and knowledgeable Microsoft producer called Rick Martinez," explains Dene. "His comedy tastes ran to Blackadder and Monty Python, so when we said we wanted to make a dark fairy tale with Pythonesque elements, he understood. We were so grateful for his help, especially when you consider another Microsoft producer heard what we were doing and said: 'A fairy tale? Like with f**kin’ singing bugs and shit?' Rick is also the guy who kicked our asses and told us to focus on the combat more. ‘You’re going to be fighting at least 60% of the time. You should be focusing at least 60% of your effort on that!’ Like many people, without his support there’d have been no Fable."

Another Microsoft producer heard what we were doing and said: 'A fairy tale? Like with f**kin’ singing bugs and shit?'

Simon is also keen to stress Martinez’s stellar contribution to the project. "It seems obvious now, but Fable was a very odd, British game that non-Brits struggled with conceptually, and Rick was able to win over skeptical Americans. Josh Atkins, at the time a senior game designer at Microsoft, also shared our passion for Fable, and was immensely helpful in cleaning up some of the floppier design elements. All in all, Microsoft were the perfect publishing partners on Fable. They were supportive, understanding and – most importantly – trusted the team."

Ironically, while Microsoft’s support was vital in shaping the final game, its desire that Fable hit store shelves in 2004 caused a considerable amount of friction within the team. To speed things up, the decision was made to involve Lionhead more closely for the final 18 months of development. "Big Blue Box at the time was about 16 people, and while we were making good progress, it was a small team for such a big game," remembers Simon. “Microsoft became increasingly keen on shipping Fable, and Fable quickly became the most urgent project that needed finishing at Lionhead, so we made the decision to combine the Lionhead and Big Blue Box teams to get Fable finished. This made practical sense but, in hindsight, the cultural impact of going from 16 people to 60 was much higher than I anticipated; Lionhead staff resented being pulled off of their own projects, and Big Blue Box staff felt they’d been assimilated into a company they hadn’t signed up to. It’s something I wish I’d handled better." The relocation of Lionhead staff predictably caused some headaches. "When it got to panic time and us shipping at all was looking rocky, I think it was all hands on deck for them – there were some people who understandably didn’t sign up to make a Fable game near an angry swan in Godalming," laughs Buzugbe.

Comments 6

Interesting piece. Even a mention of Dungeon Keeper gives me warm fizzy feelings in my stomach.

That was a fantastic read! Very well done with the article! I love Fable so much. Honestly I think I have the best memories with Fable 3 as I made a really good friend on that game & we did everything together on there. I even enjoyed Fable Heroes and I tried to enjoy The Journey as best I could. Kinda hard when the Kinect wasn’t easy to cooperate with you correctly. The heads of Xbox back then were aholes by pushing it into multiple games. I was so angry when Lionhead announced that Fable Legends (of which I still have installed on my Xbox to this day) was being shut down & later that they were closing. What a waste. Hopefully PlayGround are working on Fable IV & it’s a return to form for the series.

also heard he has a new kick starter for his virus cure that also comes with VR headset and 12k

Awesome read! Well done on the article! 👍🏻

Amazing article and a great read!

Fable is one of gaming's greats, cannot wait for a return to it's world.

If we can get a return to form for Halo AND Fable that'll be worth the Series X price right there

Really interesting read, thanks! As someone who’s never owned or played an Xbox, I didn’t really know anything about Fable’s development and always assumed it was a Molyneux game, so I’m glad I know better now! If I were to ever get an Xbox, Fable would be one of the first games I played on it.

Tap here to load 6 comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...